Connecting through Digital Storytelling

Abstract

What is particular to the culture of our time is the pace at which everything changes. The moving image is entrenched into every part of our lives. We not only rely on it to entertain us; we also expect to be able to interact with it and participate in its making, whether as consumer or content producer. The moving image has become the ubiquitous lens through which we view the world, and through it we explore and understand ourselves, other cultures and societies, experiences and places. It helps us shape our identity.

The Australian Centre for the Moving Image is a cultural institution situated in Melbourne and dedicated to the moving image. It is a place where the moving image is presented in all its forms, with a charter to research, create, collect, exhibit, teach, nurture and advocate the use of the moving image in all areas of society. It is one of the few centres of its kind world wide.

This paper charts the development of the Digital Storytelling program at ACMI. In doing so, it captures some of the understandings gleaned as a result of being one of the first cultural institutions to develop a major user-generated content program, and identifies the challenges for the organisation in ensuring this program stays relevant in a rapidly changing media landscape.

Figure 1. Image of Flinders St Entrance ACMI. Photographer David Simmonds.

Introduction

Since the organisation’s inception, I have had the privilege of developing the digital storytelling program at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI). Our intention from the outset was to deliver digital storytelling as a major program for the public and education sectors at a scale that included exhibition and long-term collection of this user-generated material.

Specifically, digital storytelling at ACMI is the process of assisting people with little or no media experience to produce meaningful stories from their lives as short format audio-visual works. These stories capture a profusion of ideas and emotions from the storyteller’s life that, when edited as a narrative, assist in documenting and telling a life story. Our aim with the Digital Storytelling program—and indeed all of our production and exhibition programs at ACMI—is to join in an open, innovation network to learn from and be active as a co-creative partner with the communities we serve. What has resulted from this connection is the creation of a new ‘meeting ground’ for both the cultural institution and the public.

ACMI regards the role new media plays in the cultural ecology as essential and sees traditional and new media as deeply interconnected. One of the strengths of the ACMI digital storytelling program is that this new media program is contexualised alongside the more familiar traditional media forms. When the organisation was developing its digital storytelling program there were very few programs in the world to act as models. The Center for Digital Storytelling (CDS) had established digital storytelling in early 1990s and was a major influence on ACMI’s program development, but the organisation does not have a public charter to collect or exhibit moving images. The BBC was developing its digital storytelling broadcast model with the Capture Wales project at the same time ACMI was developing its program, but the BBC as broadcaster had a significant infrastructure in place. It was a long and complex journey developing a user-generated program in a major organisation at a time when there was little or no precedent for this amateur content being produced, exhibited and collected in a moving image cultural institution.

ACMI did not produce its program in isolation (obviously CDS was an influence), but the organisation’s history with the moving image and in particular its screen education focus was invaluable. Melbourne itself has a long and significant history with community media practice through community broadcasting, media training centres and a wealth of community filmmakers and film video and new media independents and collectives to draw inspiration from. The technical delivery of the program was quite simple but the program development required for managing the licensing, collection and the exhibition of an ongoing user-generated program at this scale was complex.

Between 2004 and 2006 there was a significant uptake of the digital storytelling model employed at ACMI both nationally and internationally, with many educational, cultural and community organisations delivering the form within curriculum or as a community development practice and as part of the new convergence broadcast model. Increasingly in this YouTube era, the broader public has a better understanding of the notion of user-generated content. With the extraordinary pace at which technology has developed this particular media form, user-generated content has—in a relatively short time—shifted from an innovative new media practice to being relegated to somewhat of a ‘heritage’ media form.

This paper reflects on, firstly, the practice of the mediated content program over the eight years ACMI has developed and delivered the program. Then the paper considers where the program might sit within the current and constantly changing online environment. Finally, the role an organisation such as ACMI might have in the future of Digital Storytelling as a practice is discussed.

Figure 2. Photo of ACMI box office. Photograph by David Simmonds

Digital Storytelling at ACMI

The Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) is a cultural institution dedicated to the moving image in all its forms and is situated in Federation Square in the heart of Melbourne. ACMI developed from the Victorian State Film Centre, which was established in 1946 with the role of maintaining a significant collection of feature, documentary, independent and educational films for the people of Victoria. The State Film Centre also developed a major education program from the late 1980s, designed to provide a valuable interface between the collection and the secondary school curriculum through screenings, lectures and workshops for students and teachers. The State Film Centre began its transformation into ACMI in 1997 and opened to the public in 2002.

ACMI’s key objective has been to broaden the public’s access to and engagement in the art of the moving image. This is achieved through presenting a schedule of programs that includes exhibitions, film screenings, talks, forums, education programs, production workshops, performances, community activities and events and by providing access to the film collection. The programs celebrate the convergence of art creativity and technology. ACMI was evolving at a time when technology was starting to transform the way people were communicating and consuming media, so it was crucial that the Centre recognise this shift and conceive a range of programs that would very directly engage the public as co- creators of moving image content. Thus, many of the programs include hands-on production experiences, designed to create opportunities for the public to draw meaning, ideas and emotions from the conjunction and overlay of sounds, images, time, texts and contexts through a range of media applications.

In 1999, I met Joe Lambert from the Center for Digital Storytelling (CDS) at Berkeley, California. As the CDS program had a strong resonance with what we were already developing for ACMI, Joe Lambert and Nina Mullen, co-founders with Dana Atchely and then directors of CDS, travelled to Melbourne to share the CDS methodology with the ACMI team. The CDS three-day workshop delivered introduced ACMI to the potential of an autobiographical workshop program. We went on to establish a model of delivery that was translated into a moving image cultural institution in Australia.

A collaborative relationship with the Center for Digital Storytelling has existed since this initial training. I joined the International Digital Storytelling Association established by Joe Lambert, and—following on from the inaugural International Digital Storytelling Conference, which was produced by Daniel Meadows and the BBC—programmed and produced the second conference in collaboration with Joe Lambert. First Person, the International Digital Storytelling conference was delivered at ACMI in early February 2006. The aim of conference was to bring a wide range of media practitioners together to explore the developing applications of the form in the areas of community cultural development, community memory capture, oral history practice and new broadcast models within an ever changing media and technology landscape. It was a fully subscribed conference and helped cement ACMI’s leadership role and Australasia’s interest in the form.

Figure 3. First Person International Digital Storytelling Conference brochure—ACMI (http://www.acmi.net.au/first_person.aspx).

Today the term ‘digital storytelling’ has broadened to include many other media formats and story structures beyond linear first person accounts. In Digital Storytelling (2004), Carolyn Handler Miller notes that the term embraces all forms of storytelling in digital format. This means that vlogs and blogs, video and online games and sophisticated transmedia story structures or mobile devices utilising locative technologies all fall into the category of digital storytelling.

ACMI, however, still continues to define its digital storytelling as a mediated workshop program that assists people to create linear first person narratives. Any perceived limitation in this type of program definition is balanced by the broader program offered at ACMI, which gives people access to a range of innovative and interactive programs across all media forms and new and emerging technologies.

In fact one of the real strengths of the ACMI program is that the content is produced, exhibited and collected alongside all other forms of media. Apart from the obvious connection with the moving image, there is another context for the organisation to champion the form. It can be said that the moving image, as an art form, has been at the forefront of the quest to recapture and retell moments of significance. Ross Gibson, the first Creative Director of ACMI, notes in Remembrance + the Moving Image that ACMI can be seen as “a memory palace; a place where remembrance happens everyday”. Digital storytelling, through the process of associative linkage and active recall, assists people to tell important stories from their lives as moving image memories. ACMI continues this moving image obsession with remembrance through the digital storytelling program by enabling people to create and share their own screen memories.

ACMI also stands by the strength of the workshop methodology and, reflecting on our history of delivering this program, it is this ‘workshop’ production process that is the crucial component to the program’s success. The public courses at ACMI include a three day public workshop and a four day ‘train the trainer’ program and for educators a specific digital storytelling program known as ‘My Story’. The train the trainer and the educators’ program has equipped many individual practitioners and representatives from many key Australasian cultural and educational organisations to develop a program or practice within the context of their own organisations or community. Alongside these public offers ACMI also works in partnerships with very diverse communities to develop specific digital storytelling projects. This aspect of the program is significant and over the years has produced the majority of the content exhibited and collected.

Figure 4. Production Studio at ACMI

The way ACMI delivers the workshop program may well differ from others because of our focus on the screen based elements that make up a moving image story. Whilst many stories created at ACMI are strong examples of digital storytelling practices for community building and advocacy, the primary focus of the program is still on engaging people with the moving image. Framing and montage become the creative drivers and the screen literacy tenants of the workshops. Participants learn about the dramatic moment, point of view and voice. They discover that audio is more effective than text for creating a sense of co-presence, and the workshop sets out to help people grasp arc and narrative perspective by translating an abstraction into visual story. They learn about the narrative power of visual imagery and sound and how these elements layered together underscore the dialogic relationships inherent in expressive media.

Joe Lambert has written about the CDS model and discusses the importance of a restrained use of media production (see http//www.storytelling.org/coremethod.html). ACMI recognises that a short workshop with largely untrained participants has some limitations, but as a screen based organisation we are most interested in how vision and sound integrate into the storytelling arc. To this end, ACMI has built a large creative stock sound and image library for participants to draw on. Compared with other organisations, ACMI also has a large staff to participant ratio which ensures that ACMI is offering strong content development support with skilled production staff. For the projects we produce in partnerships with community, ACMI also spends some time post-producing the stories to ensure the best screening quality possible.

The combination of process, product and exhibition also gives participants the sense of shared purpose which is so important to the workshop experience. We encourage participants to listen intently and actively to one another as they create their work. Workshopping the script pulls the group together in a common, deeply personal enterprise. It is a very edifying and often a deep learning experience for the participants as they connect to the process, to each other and to the ACMI team. The following are examples of the feedback ACMI receives, underlining the intensity of the process for participants and the importance of the relationship built through the workshop environment:

I can’t say enough about how easy the ACMI team was to work with and the way they treated and worked with the participants, respect and dignity just doesn’t capture the working relationship that developed between the team and the participants … thanks for the opportunity to be involved in the process, it was an experience that has touched me and will stay with me… (participant from a community partnership project workshop)

There were so many things that made it a treasured experience for me that I don't know where to start … or end. I was blown away by the power of everyone's stories and I know that we wouldn't have been able to achieve our precious final products without the technical and story support. Each of the staff was so supportive, sensitive, respectful, real and professional … This has been a liberating thing, and to think that some people think technology is soulless. Bah. (participant of a general public workshop)[1]

Figure 5. Image from the story Mallee Bloom by Maureen Barry which is part of the Against the Grain Digital Storytelling Project.

Over the years, we have assisted hundreds of people to tell important stories from their lives as moving image memories. There are many projects that merit specific case study in the body of work we have helped produce over the years, but too many to mention in this paper. The breadth of the task has seen us work with, for example, those who have survived or are living with health conditions including mental illness, and with reformed perpetrators and survivors of domestic violence, sufferers of dementia, HIV positive men and women, and survivors of breast cancer. These projects have connected sufferers and survivors with their creativity, providing them with an opportunity to use their story and their voice as a centrepiece for health prevention and social justice efforts.

We have facilitated stories about migration and settlement, and worked with people who have been made redundant from jobs and those that have survived and or are coping with the impact of natural disasters. People have told stories about the important people in their lives, about their travel, their passions and obsessions, their sense of place, and have even shared stories about their pets. People have told meaningful stories about all possible aspects of their lives. ACMI sees its role as vital in being able to assist people to tell and share these stories. In particular it is important to help facilitate the telling of difficult stories and those that are not often heard. Some of the hardest and most complex stories in Australia surround the country’s history with its Indigenous people.

In Back of Beyond: Discovering Australian Film and Television, archivist Michael Leigh, in his essay “Curiouser and Curiouser”, speaks of Australian cinema’s keen interest in Indigenous people. Since its beginnings in the 1890s, a staggering 6,000 or more films have been made that included Aborigines as subject matter (although very few had an Aborigine in a key creative role or controlling the representation). Leigh noted that regardless of the amount of content produced about the subject, the white community was largely ignorant of Aboriginal culture, stating that the “… problem has lain with the types of representation—or, rather, the misrepresentation—exhibited by film makers for almost a century…” (1988: 78-89).

The 1980s saw the establishment of community media organisations, many in regional Australia, that were formed by Indigenous people to ensure Indigenous control of their content and programming. Community media has the ability to develop skills in media literacy and collaboration, as well as facilitate invaluable community dialogue and cultural expression. Digital storytelling is part of this broader community media strategy in that it allows community involvement, engagement and control over media content creation. User-generated content offers another important media form in which Indigenous Australians can continue the fight to have their stories heard as a way to counter lateral racism. One of the major foci of ACMI’s digital storytelling program in the last few years has been in training several key Indigenous organisations and filmmakers in the digital storytelling methodology. Along with the content we have helped facilitate with Indigenous communities, and in the context of the ACMI exhibitions and screening and collection programs that feature Indigenous content, ACMI takes on an industry role in supporting Indigenous screen practice.

Figure 6. Image from the story Life and Learning by Tim Kanoa which is part of the Koorie Heritage Trust Digital Storytellling Train the Trainer Project.

Opportunities, Challenges, and Impact

The real challenge for the organisation, when it embarked on delivering this program, was to start thinking about what was needed to produce, exhibit and collect this kind of content. There were a great number of infrastructure issues to work through to ensure we could meet all the rights and legal compliance requirements for screening and collecting content in a public moving image institution. This in itself was a protracted journey, eventually requiring legislative change to allow a cultural institution to exhibit this kind of unclassified material responsibly. Of course, this is in complete opposition with how user-generated content now works, as new technology allows for instantaneous story capture and publishing. The sort of user-generated program that ACMI delivers may not be considered particularly ‘current’ or even relevant, and time may well render this particular ACMI production program redundant. However, judging from the ongoing success of this program, there is still a role for this more mediated content-making experience.

ACMI has not formally researched the impacts of digital storytelling as a community engagement tool (the formal research is done very ably by my academic colleagues working in this area). We have, however, formed a strong view of how this program works through the experience of delivering digital storytelling over many years and in very diverse community settings. Time and time again the workshop process proves to be positive, engaging and collaborative for those involved and supports the ongoing requirement for a mediated content making process.

A major revelation for the participant is that the digital story has another essential role to play; it contextualises the content within the participants’ lives and the wider world, making it a key instigator for a strong community building process. The power of the medium for those who participate in a workshop lies in the process of sharing their personal stories with each other, within their own community and with the broader public. I have also seen people ‘put themselves out there’ for others to see, contemplate and even judge. Creating a digital story leaves people exposed to the world, and, in doing so, forces them to examine themselves. It is a complex and rewarding process and well beyond a simple 101-technology workshop experience.

The digital storytelling program supports the notion of participatory culture in a way that allows communities to find a ‘voice’. Such a program also enriches the lives of participants by enabling them to draw upon and develop their own creativity in the process of exercising this voice. As the user-generated content movement continues to develop new modes and aesthetics in storytelling, I still think it is the capacity to search for meaning and justice through people telling their own stories that is important. While there are far more sophisticated and interactive story formats, the need for communication, narrative and storytelling remains as strong and essential as ever and these simple linear works achieve this so powerfully.

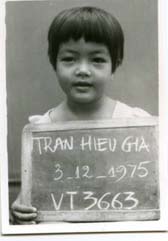

Figure 7. Image from the story Changing Worlds by Mui Mui Tran which is part of the Recovering Hope Digital Storytelling Project.

Instrumental in each community digital storytelling project we develop at ACMI is the relationship with the particular community organisation. For instance, the organisation identifies and canvasses community interest in the project, providing the relationship bridge between the storytellers and ACMI. The partner organisation also manages the long-term strategy for the content within the respective community, providing support to the storytellers after the project is complete. It is the strong partnerships created in this program that offer the real opportunity for the Centre in that it provides the grounds for a co-creative relationship that allows ACMI to very genuinely connect with its audiences.

These community organisations also utilise the content to great effect as powerful advocacy tools for raising awareness of the issues that are particular to the community. For example, Alzheimer’s Australia use stories to provide a valuable resource for people diagnosed with dementia. Other organisations have used stories to help recruit volunteers or express the organisation’s efforts in a human and meaningful way. The stories are screened in countless forums and conferences and are on many organisational websites. Over the years, the stories have been featured in major promotion campaigns, they have screened in festivals, they have won awards, become content in exhibitions and been showcased in community screenings; they have also been broadcast on television and many of the stories live permanently on YouTube.

Beyond the very practical ways in which the community distributes and uses the content, ACMI does ensure that the stories have a significant reach through exhibition to the public. As well, the content is available online and in curated screenings and exhibitions at the Centre. They are also permanently available in the Australian Mediatheque, a new exhibition and research space at ACMI that has been developed in partnership with the National Film and Sound Archive. I am always impressed by the numbers of viewers that respond to these autobiographical stories when they are exhibited. The public is genuinely inspired by the possibility that they too can produce a moving image story, regardless of their particular technological skill (or phobia).

The capacity and impact of digital storytelling is certainly exemplified in a 2007 project we collaborated on with the Latrobe Valley Council and the Gippsland community in Victoria. In 2006, fires raced through Gippsland, destroying a great deal of property. Steve Tong, Manager, Community Support and Development at the Latrobe City Council, was aware of our digital storytelling program and saw the potential benefits of developing a digital storytelling project with survivors of the bushfires in the Gippsland region to assist them in the recovery process. Tong envisaged broader screenings of the content in all areas affected by the fire to maximise the impact. From the Ashes is the result of this collaboration; it won an Emergency Services award in recognition of its community rebuilding capacity.[1]

On the strength of the stories created in the From the Ashes project, we have recently collaborated on a major education project with the Attorney General’s Department. Stories from young people who have survived natural disasters, including those who survived the Black Saturday fires in February 2009, are the basis of a major curriculum resource, which includes lesson plans developed around each of the stories. This project has been designed to assist secondary students and teachers understand the importance of preparation for natural disasters.

Figure 8. Image from Black Saturday fires February, 2009 Murrundindi Victoria which is part of the Living with Disasters Digital Storytelling Project in partnership with Attorney General's Department and the CFA. Photo curtesy CFA

Due to the increased accessibility of technology, many organisations now have the capacity to develop their own digital storytelling projects and to distribute these online, without the help of a media based organisation like ACMI. Furthermore, over the years ACMI has trained many community organisations in the digital storytelling methodology, enabling them to sustain this approach to content creation. The in-built training pedagogy of the program supports sustainable practice and also means that the direction of the ACMI digital storytelling program will shift with time.

ACMI will continue to explore the many different kinds of media—both traditional and new, including different styles of user-generated and co-creative content models—in the breadth of programs it delivers. While our current strategic efforts are still directed towards helping other organisations and the broader public to mine tremendously powerful stories, our content development focus is on ensuring an ongoing and strong contextual distribution of this content. Currently we are structuring projects that also develop curriculum and resource material around stories to support the impact and reach of the content through education channels and are in conversation with broadcast partners to extend the distribution reach.

The context for the stories also includes more interactive resources that sit along side these linear stories for the education sector as a way to facilitate a more engaging learning process for students. For example, with Veterans Affairs and the Shrine of Remembrance, we are working on a project that will see us capture the stories of more than 200 Victorian war veterans over the next four years. A major component of this project is designing and building interactive production templates, including ‘how to’ resources, and making available stock libraries so students can respond to the linear material to repurpose the content through various types of content creation modes, including mash ups and the production of their own digital stories. This contextual material ensures a more active engagement with the linear works within the web 2.0-environment.

Arguably, some of the most interesting media projects happen outside of institutionalised spaces. Nevertheless, a moving image cultural organisation does have a role to play, in order to keep contributing to both the user-generated content movement and the online dialogue. The role of a moving image organisation is to set a context for the production; ACMI’s collection of moving image memories is not simply an exercise in nostalgia, nor is it just a process to memorialise. Rather, we are ensuring an individual and collective register for moving image memories as a way for these stories to be shared and disseminated. ACMI has accumulated one of the largest systematised collections of digital stories in the world. It is hoped that in the future the ongoing exhibition and collection of content will make a significant contribution to future discussions and debates about user-generated content.

Figure 9. Image from a documentary interview with Norm Smithelles which is part of In Our Own Words; Stories from Victorian Veterans Project in partnership with Department of Planning and Community Development and the Shrine of Remembrance.

Footnotes

[1] For further examples of collaboration with participants and organisations, see the ACMI methodology section of the website http://www.acmi.net.au/digital_stories.htm

[2] See http://www.acmi.net.au/dst_bushfire_stories.htm

References

Handler, C. (2004). Digital Storytelling: A Creators Guide to Interactive Entertainment. Burlington: Elsevier.

Gibson, R. (2003). Remembrance + the Moving Image. Melbourne: ACMI.

Leigh, M. (1988). Curiousier and Curiousier. In Back of Beyond: Discovering Australian Film and Television. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA.

About the author

Helen Simondson is the Screen Events Manager at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image. Email: [email protected]

Facebook comments