Electricity Prices – Cause For Concern

Most readers would be well aware that electricity is a material expense that has been increasing for all consumers.

If you follow the energy debate in the mainstream media, then you have probably drawn the conclusion that failure of policy at national and State levels has been a key contributor – and this is somewhat close to the reasons for the current price hikes being experienced.

Governments of all persuasions at Federal and State levels have not been able to establish an enduring policy setting to provide the basis for investment in what are long lived assets required to provide an affordable and reliable supply of energy.

This situation has been exacerbated in recent times by the supply and demand for gas and in particular the impact that significant gas exports on the eastern seaboard is having on domestic gas prices and medium to long availability.

As gas generated electricity is often the marginal generation required to meet demand and seen as the transitional generation to a lower emissions future, the domestic gas price has had a material effect on current and forward electricity prices which are trading at unprecedented levels.

It is the forward prices of electricity that underpin the pricing that retailers offer to end-use customers.

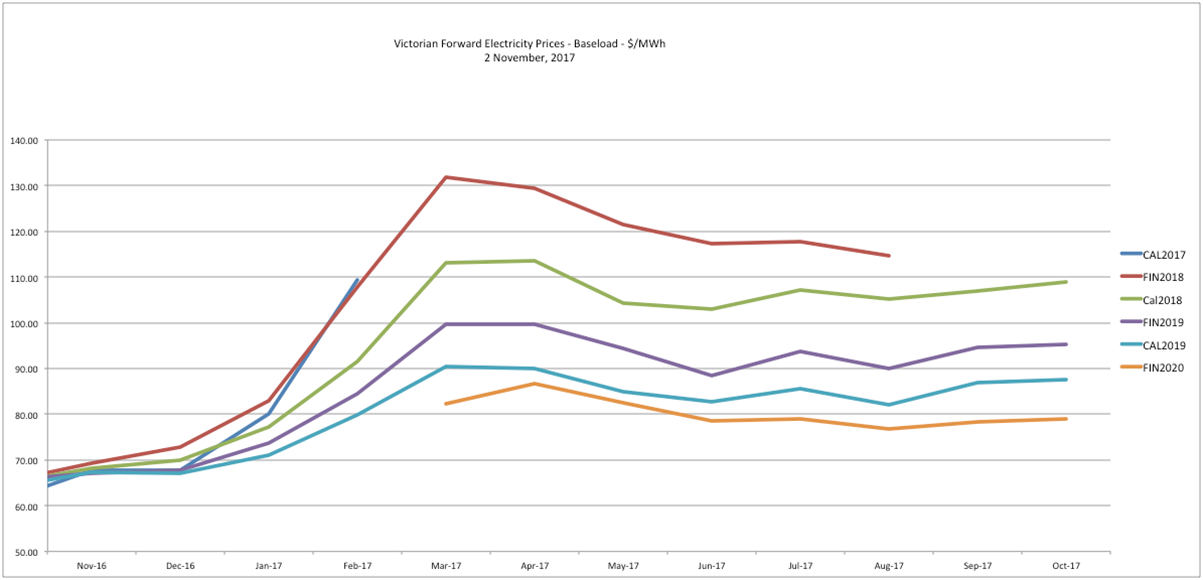

At the time of writing, Victorian base-load prices for the next year are above $109 per megawatt-hour (MWh) whilst three years out, the forward price is above $75/MWh.

Since the establishment of the National Electricity Market (NEM) in the late 1990s, wholesale electricity prices generally stayed in the range of $25/MWh to $55/MWh, excluding the period earlier this decade when a carbon price was added by the Gillard Government. The chart below shows the annual Victorian forward electricity prices over the past year for calendar year (CAL) and financial years (FIN) ending 30 June.

In simple terms, electricity costs to consumers are mainly driven by wholesale electricity costs, network charges (both high voltage transmission and low voltage distribution) and a range of bundled costs including renewable energy subsidies and retailer margins.

Traditionally, the most significant of these costs has been the network charges – which are determined by Government regulators which control the investment programs of various network owners to maintain reliability standards. It is commonly observed that regulators have allowed such programs to produce “gold-plated” network assets at a significant cost to electricity consumers.

Now that wholesale electricity prices have risen to unprecedented levels, the imposition on top of the already high network charges is causing much concern for industry and those in lower socio-economic situations; and all this without a price on carbon emissions at this time.

Productivity Commission Report

The Australian Productivity Commission has also recently completed a review on the state of nation’s energy markets and some of the key points it made reinforce the concerns of industry. It states that:

Australian energy markets, particularly those in eastern Australia, are in a fragile state. While the statewide blackout in South Australia, on 28 September 2016, was initially caused by nature, the duration of the blackout brought issues about the security and stability of the national electricity grid to the fore.

The estimated cost of the statewide blackout in South Australia was $367 million. With electricity and gas making up 2.5 per cent of GDP, and being an essential input for all industries, the cost of failure to resolve the problems will only rise in the future.

It is too difficult to put a price tag on getting energy policy right, in large part as the counterfactual — what would happen if we continue to try to muddle through without clarity on carbon pricing — is impossible to define. Nonetheless, the returns from the reforms outlined here would be worth many billions.

Lack of clarity on emission reduction policies, increasing reliance on intermittent and variable renewable energy, moratoria on gas exploration and development, and the commencement of gas exports from the east coast, have all contributed to a system under pressure.

The challenge is how to resolve these issues while maintaining an affordable, reliable and sustainable supply of energy going forward — dubbed the ‘energy trilemma’ by the recent Finkel Review (2017)."

Significant policy and technical work has been undertaken in response to these challenges, of which the Finkel Review is the most recent. Finkel set out an approach that seeks to find an option, amongst many, that is politically palatable.

The issues affecting the sector are complex, and their solution requires considerable technical expertise as well as good regulatory and institutional design.

This requires solving the immediate problems, but also needs to be mindful of transforming the energy system so that it will deliver for consumers in the long as well as the short run.

The Australian Productivity Commission review goes on to outline what it considers to be the key requirements that Government must address – including:

- A national agreement on simple, clear objectives — that recognise the inherent tensions between prices (costs), reliability and emissions, and provide guidance on acceptable trade-offs — then leave the field to expert implementation,

- Determining which institutions do what — then let them get on with their work, holding them to account for their stated responsibilities,

- Ensuring that the energy sector can access the full set of instruments in doing their work — not locking in or out technologies, or excluding other solutions by design,

- Setting out a clear roadmap for reforms — ideally with cross-jurisdictional commitment, and

- An emissions target to provide certainty for the sector about the trade-offs allowed between emission reduction and cost.

Energy Security Board

It is noted that the Federal Government has recently announced a new approach following work undertaken by the Energy Security Board (ESB) that was established by COAG. According to the ESB report, the Federal Government had asked this body to provide:

“advice on the changes needed to the NEM and legislative framework to ensure that the system provides reliable, secure and affordable electricity, and in particular, ensure that:

- The reliability of the system is maintained;

- The emissions reduction required to meet Australia’s international commitments are achieved;

- The above objectives are met at the lowest overall costs.

The ESB response came in the form of a Reliability Guarantee and an Emissions Guarantee. The key features of these mechanisms are as follows:

- The Reliability Guarantee would require retailers to hold forward contracts with dispatchable resources that cover a pre-determined percentage of their forecast peak load and be based on the system wide Reliability Standard as determined by the Reliability Panel at the AEMC. At the beginning of the compliance period, retailers and large users would be required to provide evidence to the AER (Australian Energy Regulator) that their contracts met the requirement.

- The Emissions Guarantee would involve an emissions target being set by the Commonwealth Government in line with international commitments and this target being translated into requirements to be met by retailers and large energy users in terms of average emission levels. Again, compliance would be undertaken by evidence provided to the AER.

This proposal has received mixed reaction from financial, industry and environmental groups. However, most notably, the States have not reacted positively and any scheme for NEM implementation would require the full support of COAG which seems problematic at the moment.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that the nation is in dire need for an enduring and robust energy policy, it is unlikely that Australia will see this in the near future. Recent history suggests that a bi-partisan approach would now be required to deliver this. However, given the divisions within the Federal Coalition (on environmental issues in particular) and the fact that the Government is unlikely to be returned (based on media polling and commentary), a bi-partisan approach would remove a key point of difference between Labor and the Coalition and is therefore unlikely to be achieved in the near future.

The need for strong leadership and a clear mandate from the electorate will be the pre-requisites for the establishment of an energy policy that can meet the needs of the Australian people.

What Does All This Mean For Community Broadcasters?

Clearly, there is not going to be any significant rate relief on electricity prices in the short term. Consequently, community broadcasters need to:

- Shop around for the best deal you can get on electricity – and beware of those retailers offering discounts where you do not actually know what peak and off-peak rates you will actually pay,

- Consider using an independent energy advisor to source the best deal for you – some operators are reputable and fees are modest in some cases – my station has used such a company in the past year,

- Explore what demand management activities or energy efficiency gains you can make to shift or reduce demand,

- Re-consider the economics of alternative power supply.

By Ken Thompson of 3GCR (current CBAV advisor on electricity market issues). This article was originally published in the November 2017 CBAV newsletter.

Facebook comments