The Re-creation of Identity in Digital Environments and the Potential Benefits for Non-Profit and Community Organisations

Abstract

As the early 21st century society evolves into a hybrid world of digital and physical environments, a new generation of users is traversing seamlessly between online and offline dimensions in these emerging communicative ecologies. This paper explores what happens when young people re-create their human identity in these spaces. How they use the tools of new technologies to capture and share their experiences, and how they represent themselves in relation to the world they live in. We analyse the practices of these users and the changing digital landscapes they occupy to then discuss lessons and potential benefits to strengthen the ability of non-profit and community organisations to engage and interact with young people and other constituents in a Web 2.0 era.

Introduction

Information technologies are creating new sites where we establish social and cultural meanings. As a new generation of users re-create their human identity in these emerging digital spheres we need to understand how this meaning making process occurs. To do this, this paper briefly examines the critically informed texts from the discipline of cultural theory. These discourses are relevant because they have as a central focus a concern with the process through which we re-construct our identity in light of our interactions with the world around us.

Goffman (1959) describes the way in which our interactions drive us to become actors (see also Latour, 2005) presenting our desired face to the world depending on the context of the situation, and in doing so he highlights the diverse nature of identity. For Goffman, the construction of our identity evolves through a series of ‘performances’ shaped by the environment, the audience and the impression we want to make. Yet in the disembodied world of digital space, the cues to identity that we have in the real world are absent. The result is that digital identities are lent greater fluidity and flexibility. We can play and experiment with online identities that are removed from the confines of reality.

Giddens (1991), Haraway (1991), Poster (1995), Rheingold (2000) and Turkle (1995) focus on this re-construction of identity in digital environments. They find not only a strong correlation between real life and digital identity, but that digital identity breaks free from the constraints of everyday life. Haraway, in her seminal text A Cyborg Manifesto (1991) explores the concept of digital identity through the creation of the cyborg, a digital representation demarcated by its ‘otherness’ to the user’s everyday self. For Harraway, this presents the opportunity to free one’s self from the constraints of mainstream culture, especially the notion of gender stereotypes.

The cyborg is a creature in a post-gender world; it has no truck with bisexuality, pre-oedipal symbiosis, unalienated labour, or other seductions to organic wholeness through a final appropriation of all the powers of the parts into a higher unity. In a sense, the cyborg has no origin story in the Western sense. (p. 150)

Turkle (1995) in a similar vein finds that digital environments allow users to shed the human qualities of age, gender, race, disability and disease.

A distinguishing characteristic of the identities appearing in digital environments is that they are potentially more malleable than those limited by the everyday confines of the body and as Wilbur (1997) and Boyd (2006) suggest, this provides the potential to consciously shape our selves in new and novel ways.

In computer-mediated communication (CMC), the performance of identity occurs primarily not through direct experience of the body but within the constraints of digital representations constructed by interactive systems. To compensate for the loss of physical presence, people have had to create new ways of reading the signals presented by others, and new ways to present themselves. (Boyd, 2006, p. 16)

At a time when designers are theorising about the nature of user experiences in digital environments and asking as Laurel (2003) does, ‘Can we create real social depth?’ (p. 196), these perspectives provide more than academic insights into the practice of identity creation. They have a practical application, encouraging us to critically consider the implications as the digital generation extend their identity into an increasingly pervasive digital sphere. Exploring the pleasure users get from playing and experimenting with digital identity challenges the often held notion that digital identity should be thought of in terms of the restriction of information or anonymity. Our focus is directed onto how users want to reconstruct their identity in these spaces. What qualities do they want to include? What do they want to leave out? As Giddens’ states, ‘What to do? How to act? Who to be?’ (1991, p. 70).

In order to address these issues, this paper will examine two projects – The Novell Digital Identity Study and The Swarm Mobile Phone Study. Together these studies provide insights into a new generation of user and the nature of the digital environments they inhabit. We find an emerging digital ecology where users are taking control of their own creative content production and authoring for dynamic self-representation. Each study’s findings are discussed in light of its implications and potential for young people to produce a digital identity that embraces a social and political ideology and consciousness.

The Novell Digital Identity Study: Synthesising the ‘Self’

The research project was concerned with understanding the relationship between identity and technology. The focus was on the ability of digital identity management systems to align with the needs of users (Satchell et al., 2006). The study represented a sustained effort to understand and characterise identity management systems, not simply as technical phenomena, but as Dourish and Anderson (2006) emphasise, phenomena embedded in social and cultural contexts. The result was that the findings provided more than information about interface design and networking issues. They revealed a new emerging user archetype who uses virtual environments to create a digital reproduction of their own experiences.

The user study involved a mixed method approach that included ten open-ended, one-on-one interviews, two focus groups with five users in each group and a cultural probes study conducted with the five participants from one of the focus groups. The use of these three disparate methods ensured that data was collected in both a laboratory setting (semi-structured interviews and focus groups) and in the context of the daily life of the participants (cultural probes and related interviews). This enabled the collection of a rich set of data and triangulation of the data across the different methods.

The interviews were semi-structured to ensure that data collected was highly relevant and focused on user needs in identity management systems while at the same time permitting participants to elaborate on issues that emerged during the interview (Neuman, 2003). The interview protocol was based around the six key issues discussed previously together with two scenarios to provoke comment. Participants were recruited using an agency and were paid for their participation. They were each young professionals who used information technology intensively in their jobs. A total of ten interviews, each of approximately one hour duration, were conducted.

The focus groups were designed to further explore user needs in identity management systems by facilitating discussion amongst participants to encourage development of opinions by interaction between participants (Krueger 1988). The focus groups used the same interview protocols as the semi-structured interviews and involved the same participants split into two groups of five.

The interviews and focus groups were audio taped and later transcribed into digital text. The text was then introduced into N6, a computer program for the analysis of qualitative data. N6 was used to aid in the management of the data during coding – the start of the process through which the transcripts were searched for emerging themes. Once the themes had been identified, they were placed into a matrix.

Cultural probes (Gaver et al., 1999) are useful when the phenomena under study are difficult to access, or likely to be radically changed in the process of their examination. In addition to the post-hoc interviews, and focus groups, we deployed cultural probes to provide the participants with an opportunity to ‘reflect in the moment’ on their perceptions, needs and importantly, future desires. Rather than containing reliable and valid information on the current practices of our participants, the value of the probe packs came in their facility to trigger creative reflection and capture inspirational fragments. The probe packs consisted of a diary, a scrapbook, a camera, and various other items including pens and scissors. Postcards, return email addresses and SMS text numbers were provided so that the participants could contact the researchers at any moment. The probe data, consisting largely of diary and scrapbook entries and associated interview notes, were filtered for identity related issues and observations, and these instances were used as a tertiary data source.

Seamless and streamlined digital environments

Digital environments are rapidly evolving into integrated systems and mixed devices and services that include mobile phones, the Internet, digital television, gaming and e-commerce. This convergence provides users with highly personalised and tailored services. The study found that users want to create and control digital representations of themselves that are streamlined, portable across domains, devices and services, and reveal elements of their real life identity, yet this seamless transition across digital environments is not always achievable because of shortcomings in the systems themselves. For example, one of the most valued identities on the net is an eBay reputation, yet it exists purely on eBay and cannot be moved or ‘mashed’ onto other digital identities such as Craigslist (Hardt, 2005).

Translating these findings into the context of online engagement and interactions users have with non-profit and community organisations, it is desirable to move away from a piecemeal approach that segregates interests and seeks to compete for the attention (and donations) of users. A federated and concerted presentation framework for the online presence of non-profit and community organisations could allow for a much needed level of flexibility. The supporter of climate change research and energy conservation can at the same time be a vegetarian and proponent of human rights. The ability to make people’s contributions across different players in the sector transparent could entice a larger proportion of people to follow suit. It could also encourage people to build a portfolio of engagement activities according to their breadth of interests and beliefs rather than to be limited by their ability to manage multiple roles online. Design solutions could include frequent flyer types of schemes that reward contributions across the sector and provide peer recognition of time and effort.

Trading security for creativity

In this study, multiple identities were an important part of the users’ experience in digital environments, however, for the participants in the study, this did not translate to the need for disparate or separate silos of data. Rather, there was a need for the fragments to be moored to the user’s central self. Even when users professed an ideological opposition to organisations compiling data about them, in practice, they were actually quite blasé about revealing information for the sake of greater self expression.

The disjunction between the need for security versus the need for more dynamic digital identities was not insignificant. The research revealed that it comes at a time when there is a distinct shift as young people move away from the ‘big brother’ Orwellian notions of privacy that characterised the baby boomer generation. As the risks become well established and are understood, a new generation of users tend not to react strongly to concerns about digital identity theft or misappropriation. Increasingly savvy users know that financial losses due to crime such as stolen credit card details are generally shouldered by the institutions such as banks. Furthermore, the impact of loss of reputation due to the unauthorised access and dissemination of personal information has become diluted in a society saturated by digitisation. There is also a trend towards disillusionment that some random informal Facebook chats are private but not necessarily relevant to the concerns of nation states. Simply speaking: If the FBI and CIA want to read my MSN chat logs, what value do they get out of it? If there is no purpose/value, why would they care? And I have done nothing wrong and thus I have nothing to hide... Notwithstanding these findings, the imperative to safeguard personal information will remain crucial for many sectors in the non-profit and community industry - health-based organisations dealing with confidential information about someone’s HIV status for instance. However, when it comes to seemingly mundane information, an overly restrictive security policy can kill engagement, creativity and initiative in its infancy. Many young people express concerns for civic and environmental issues through their online identities and presences on blogs, profiles on social networking sites and photo and video sharing sites. Rather than being repelled by concerns over a loss of control, boundlessness and security, it is worthwhile exploring ways to reach out to a young audience on their terms and using their language and media. Some non-profits have started to experiment with organisational profiles online as a way to provide entry points to show solidarity and start a dialogue between young people and the more formally initiated campaigns and programs being offered by the organisation.

The Swarm Study

The Swarm mobile phone prototype was developed in response to the users’ needs identified in a three-year study (Satchell & Singh, 2005). It took cues from user led innovation and extended to the user multiple avatars that allowed individuals to define and manage their own virtual identity. They provided contextualization and personalized information, and allowed users to maintain a constant digital presence without the intrusion that continuous connectivity could bring.

Thirty-five technologically competent users, 18-30 years old, living in Melbourne, Australia participated in The Swarm study. The method of the open-ended interview (Minichello et al., 1995) was used to conduct the study. Grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) was used to analyse the data and cultural theory concepts were engaged to help in the process of translating use into design (Satchell, 2008).

A series of four user problems and four design implications emerged that resulted in the basis for the Swarm mobile phone prototype.

Users are disconnected physically but connected digitally

Young people are living increasingly fragmented lives; despite this, it has been shown that mobile phones can provide cohesion by providing a virtual space where interaction can occur. How can a future mobile phone do this more efficiently?

The design response suggests The Swarm as a virtual lounge room that resides on a mobile device. It is always on. The user is represented in their virtual lounge room by an avatar. The avatar represents the user as being engaged in a specific activity. This allows the user to maintain a constant virtual presence. The Swarm provides the user with a virtual home base on their mobile phone so no matter where they may be physically they are still in one place digitally.

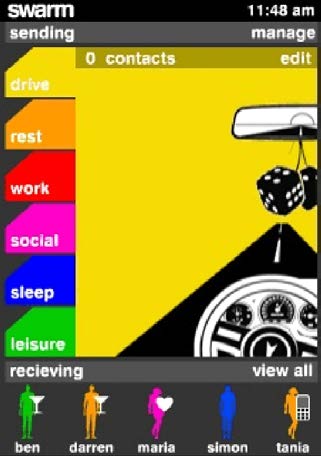

Figure 1: The Swarm main screen. The main avatar represents the user of the phone and what activity they are engaged in, for example, in this case the user is driving. The small, colour-coded avatars at the bottom of the screen represent the user’s friends.

Similarly, many small activities, steps and initiatives that people engage in civically may be too small to track, count or take notice of. Design solutions for reaching the constituents of non-profit and community organisations might call for a virtual acknowledgement room that offers a space for recording the contributions made by individuals not only as a way to commemorate these efforts, but also to showcase them as a means to provide a positive example for others to be inspired.

Reducing unnecessary interaction

Users want connectivity at all times. However, this does not mean they want to be contactable at all times. A mechanism needs to be put into place that allows users to have control and fluidity over the virtual space that the mobile phone creates. Our study responded to this challenge by designing for connectivity without contactability. The avatars depict the user’s current activity and can be programmed to appear on the user’s friends’ mobile phone. As the activity changes, the avatars can be updated accordingly. This allows individuals to see at a glance what the other members of their friendships network are doing at any particular time. By providing users with this contextual information about what other members of their social group are doing, presence and intimacy are maintained. In turn, this allows users to draw on their sense of social and cultural etiquette and depending on the nature of the activity, decide if they should contact each other or not. For example, in Figure 2 it can be seen by the heart embedded in Maria’s avatar that she is on a date. This would indicate that it might not be an appropriate time to call.

Figure 2. The Swarm facilitates the creation of activity based avatars that can be mapped onto ever-changing locations and everyday events. The user can provide their chosen friends with a continual account of their activities. Ultimately, this gives serendipity a nudge in the form of facilitating interactions with individuals or groups who may be in the same vicinity (Foth, 2006).

The related key lessons for non-profit and community organisations are about the significance of context awareness. The message of the latest educational campaign will be ignored if the poster is in the wrong spot, the email arrives at the busiest time of the day, or the SMS text triggers a notification sound at the most inappropriate time. However, ubiquitous computing and pervasive technology increasingly allow for a much more nuanced context awareness. Taking advantage of these features enables promotional strategies that do not favour the quantity of mass publicity but the quality of targeted communication at the right time at the right place using the right medium.

The need for multiple identities, context and personalisation

Mobile phones are central to identity; therefore, a mobile phone needs to be robust enough to allow the user to construct different identities in a range of contexts. Users in the study modified the Swarm so the avatars were not conveying what they were really doing, but rather, what they wanted others to think they were doing. ‘I like this idea of using an avatar, I like it a lot, but, I just realised you could never use the same one for every caller. That’s what’s wrong with this design.’ Therefore, unlike notions of identity held within ubiquitous computing that aim to restrict information about the person to enhance security, a challenge instigated by users was to allow different identities to be expressed simultaneously in a range of contexts.

The project responded to this challenge by offering multiple avatars. The Swarms’ virtual lounge room supports multiple avatars that represent the users’ multiple identities. The user can set up the avatars so that they can simultaneously convey different meanings to different people. For example, one avatar conveys professional identity and the other a social identity.

Similarly, in the context of non-profit and community organisations, stakeholders and constituents have multiple roles and identities which are often not addressed individually. Online presences usually assume a collective, homogeneous audience, usually because the design response is easier. However, there are benefits in being able to offer a high level of customisation and personalisation. It is not surprising that viral marketing tactics have been successful, since messages are communicated via a pre-established trusted channel. The effectiveness of messages increases with the level of trust, familiarity and personalisation.

Figure 3: The user projects leisure mode to four people (left screen) while simultaneously conveying work mode to seven contacts (the right view).

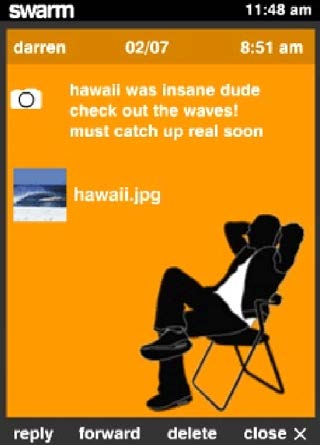

Enhancing identity with content

Users are taking advantage of 3G telephone systems and the Internet to produce and merge bits of data to create their ‘ideal digital self’ through which they communicate socially. Instead of voice or text, users are communicating through a hybrid of still and moving images, sound-bytes, and commercial content such as ring tones. With the convergence of cameras and mobile phones, users can add ‘up to the minute pictures’, creating a presence that reflects a continual digital representation of their real life.

I take digital photos and videos with my phone. Then I email them to my computer, download songs, attach it all to an email and send it to my friends. I can listen to my voice mail messages on the Internet. Then I can save them and use them as samples. Then I can email them back to friends and include pictures of them, or bits of their favourite song or something as birthday present.

Producing and sharing content is an important part of how young people share experiences. How can a mobile phone meet users’ needs for more sophisticated facilities to share their experiences through the production, distribution and display of content? Our design research came up with ways to enhance identity with content. The Swarm, which has picture and video capabilities, allows the owner of the phone to capture and display ‘up to the minute pictures’ on the ‘walls’ of their virtual lounge rooms. By doing so the owner of the phone is able to customise the look of the room and make it reflect a continual digital representation of their real life. This can act as an incentive for those not present to join them or allows for those who cannot be there to ‘get the picture’.

In Figure 4 the user notices a friend Darren’s avatar has appeared on their phone and clicks on it. This brings up Darren’s lounge room that reveals he is in Hawaii. The user can tell by the presence of the thumbnail image that Darren has enhanced his digital presence with content, clicks on the image and checks out the surf.

Figure 4: The thumbnail image indicates that presence has been enhanced with digital content (left). When clicked on it, this brings up the picture on the right. The addition of digital content allows for the sharing of experiences with those that cannot physically be there (right).

Non-profit and community organisations have long recognised the need to use a mixed media approach to convey their message. The findings from our study go a step further and point in the direction of enabling users to weave their civic, volunteer, political or community interests and activities into the fabric of everyday life. This can happen with conventional ‘merchandise’ such as stickers, coffee mugs and hats, but some new media design responses might also allow users to take digital representations of the experiences they had in their role as volunteer or community member and transfer them into those aspects of their life inhabited by their role as family member, friend or work colleague. The organisation’s ability to allow its members, clients, constituents and stakeholders to seamlessly traverse between their professional identities and their social identities will be key in order to successfully bridge the various role-to-role relationships people create and maintain. Creative content is a major conduit in enabling these transitions.

Conclusion

The two studies highlight that the digital generation want control and creativity over their virtual presence and what information they are revealing about themselves. At a time when new technologies allow the worst case scenarios described in Huxley’s A Brave New World (1932) and Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953) younger users are paradoxically, becoming less concerned about issues of digital identity theft or the misappropriation of information. Furthermore, the studies reveal that in a society saturated by reality television, personal blogs, Flickr, MySpace and Facebook a new generation of user wants to reveal, rather than conceal, elements of their real life identity, a real life which is increasingly merging with their digital life.

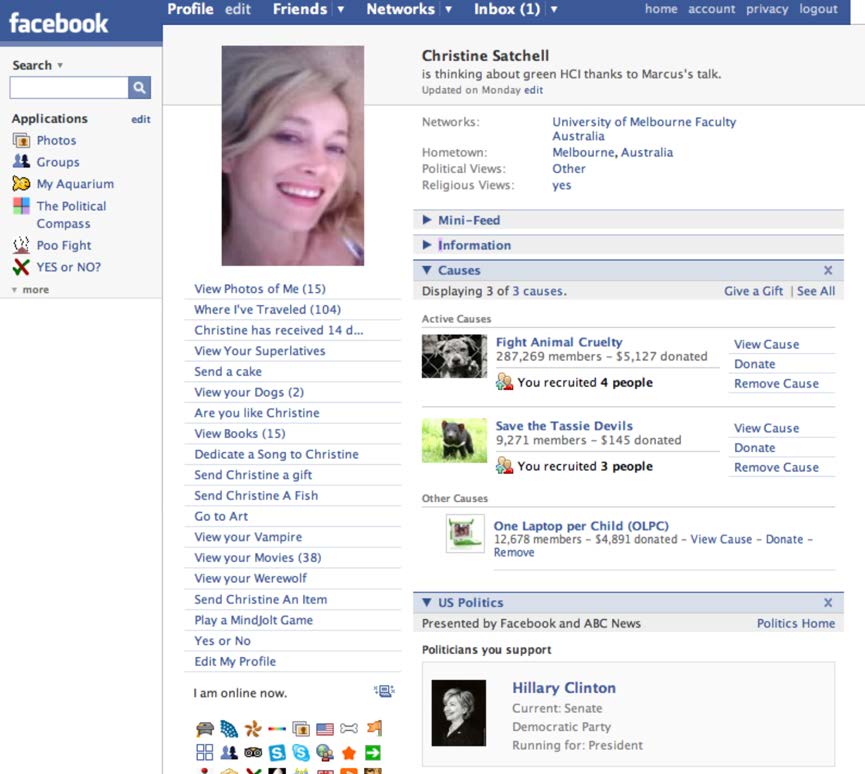

These insights can benefit non-profit and community organisations in a way that will help them interact with youth and young people for social change and community action. The digital generation seeks to create, manipulate, control, play, identify themselves, express their taste, their beliefs, political affiliations, their aesthetics, their sexuality and humor via their digital representations. The recent mass uptake of MySpace, Facebook, YouTube and Flickr provides further opportunity for these users to identify their affiliations and interests, creating a digital presence that reveals ‘This is who I am, this is what I believe in’. Although more research into this area is needed it appears that users are recreating their digital identity in a way that includes elements of political and social ideologies (Shirky, 2008). For example, a Facebook presence, which typically incorporates many fun and social applications also includes stated affiliations with a set of causes. For example, ‘Free Burma’, ‘One Laptop Per Child’, ‘Save the Tasmanian Devils’ or an acceptance to attend ‘The Australian Election Party’. This indicates that a generation often accused of being apathetic and disengaged are entering political and social debate using new technological applications to incorporate their viewpoints as an integral part of their digital identity (see Figure 5).

In a recent article in The Age (Kent, 2008) titled ‘Writing for a cause: e-activism gives politics a fresh face’ the author of this paper was interviewed about her use of Facebook to express her support for the apology to the aboriginal stolen generation.

On the day Kevin Rudd delivered his apology to the stolen generations, Christine Satchell updated her Facebook status to ‘is sorry’ like thousands of other Australians. The small virtual gesture made her position on the sorry debate loud and clear to her online friends. ‘I think it helped affirm it in myself and also showed my friends I was sorry and encouraged them to think about it too,’ she says. ‘It was really nice to see my own identity reflected back at myself on such an important issue.’ Satchell also recruited friends to the Facebook groups ‘One Million Australians Feel Sorry’ and ‘I’m Changing My Facebook Status to ‘is Sorry’ on February 13’. The historic day, which sparked a flood of virtual apologies like Satchell’s around the world, highlighted the growing clout of online political activism. For a generation often scorned as apathetic on the question of activism, social networking sites such as Facebook and MySpace have been encouraging renewed interest in the political sphere among young Australians. (p. 17)

Figure 5 shows a screenshot of a Facebook page. The user has incorporated causes she supports and people she has recruited to the cause. The user also displays her support of a particular candidate for the US election.

It can be concluded that young users are not as apathetic as traditionally thought. They just needed the tools and the medium and now they are using them highly effectively to incorporate political and social activism as an integral part of their digital identity.

References

Boyd, D. (2006, Feb 19). Identity Production in a Networked Culture: Why Youth Heart MySpace. Paper presented at the American Association for the Advancement of Sciences (AAAS), St. Louis, MO.

Bradbury, R. (1953). Fahrenheit 451. New York, NY: Ballantine Books.

Dourish, P., & Anderson, K. (2006). Collective Information Practice: Exploring Privacy and Security as Social and Cultural Phenomena. Human-Computer Interaction, 21(3), 319-342.

Foth, M. (2006). Facilitating Social Networking in Inner-City Neighborhoods. IEEE Computer, 39(9), 44-50.

Gaver, B., Dunne, T., & Pacenti, E. (1999). Cultural Probes. ACM SIGCHI interactions, 6(1), 21-29.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Polity.

Goffman, E. (1959). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. London: Penguin.

Haraway, D. (1991). A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century. In Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (pp. 149-181). New York: Routledge.

Hardt, D. (2005, Oct 5-7). Web 2.0 High Order Bit – Identity 2.0. Paper presented at the Web 2.0 conference, San Francisco. http://identity20.com/media/WEB2_2005

Huxley, A. (1932). A Brave New World. London: Chatto and Windus.

Kent, M. (2008, Feb 24) Writing for a cause: e-activism gives politics a fresh face. The Age Newspaper. http://www.theage.com.au/news/in-depth/strongonlinestrong-eactivism-gives-politics-a-fresh-face/2008/02/23/1203467451194.html

Krueger, R. A. (1988). Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Laurel, B. (Ed.). (2003). Design Research: Methods and Perspectives. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Minichiello, V., Aroni, R., & Hays, T. (2008). In-depth Interviewing: Principles, Techniques, Analysis (3rd ed.). Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson Education Australia.

Neuman, W. L. (2003). Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Poster, M. (2001). Cyberdemocracy: The Internet and the Public Sphere. In D. Trend (Ed.). Reading Digital Culture (pp. 259-272). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Rheingold, H. (2002). Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Perseus.

Satchell, C., & Singh, S. (2005, Jul 22-27). The Mobile Phone as a Globalising Artefact. Paper presented at the HCI International conference, Las Vegas.

Satchell, C., Shanks, G., Howard, S., & Murphy, J. (2006, Jun 12-14). Knowing Me – Knowing You. End User Perceptions of Digital Identity Management Systems. Paper presented at the 14th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Göteborg, Sweden.

Satchell, C. (2008, Apr 5-10). Cultural Theory and Real World Design: Dystopian and Utopian Outcomes. Paper presented at the CHI conference, Florence, Italy.

Shirky, C. (2008). Here Comes Everybody: How digital networks transform our ability to gather and cooperate. New York: Penguin Press.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Turkle, S. (1995). Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Wilbur, S. P. (1997). An Archaeology of Cyberspaces: Virtuality, Community, Identity. In D. Porter (Ed.), Internet Culture (pp. 5-22). New York: Routledge.

About the authors

Dr Christine Satchell is a Senior Research Fellow at Queensland University of Technology where she is working on the project Swarms in the Urban Village which is concerned with informing the design of Internet technology to support social networks of urban residents. She is also an Honorary Research Fellow with the Interaction Design Group at The University of Melbourne. Her research is concerned with understanding the social and cultural nuances of everyday user behaviour in order to inform design. Integral to this is the development of a methodological approach that embeds cultural theory within Human Computer Interaction. A specific focus of her research is the design of mobile artefacts.

Dr Marcus Foth is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Creative Industries and Innovation, Queensland University of Technology (QUT), Brisbane, Australia. He received a BCompSc (Hon) from Furtwangen University, Germany, a BMultimedia from Griffith University, Australia and an MA and PhD in digital media and urban sociology from QUT. Dr Foth is the recipient of an Australian Postdoctoral Fellowship supported under the Australian Research Council’s Discovery funding scheme. He was a 2007 Visiting Fellow at the Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford, UK. Employing participatory design and action research, he is working on cross-disciplinary research and development at the intersection of people, place and technology with a focus on urban informatics, locative media and mobile applications. Dr Foth has published over fifty articles in journals, edited books, and conference proceedings. More information at www.urbaninformatics.net

Acknowledgements

Dr Christine Satchell was one of the keynote speakers at the Making Links conference in Sydney, 30-31 Oct 2007. Christine would like to thank the Making Links 2007 organising committee and audience for the opportunity to present this research. She also thanks Niki Widdowson at QUT for the ideas she contributed during our conversations.

Dr Marcus Foth is the recipient of an Australian Postdoctoral Fellowship supported under the Australian Research Council’s Discovery funding scheme (DP0663854).

Facebook comments